Painting Forces: Making the Invisible Visible

Beyond representation—that is a task for our time. Why? Not simply because representation is inherently bad, but because it is merely one possibility among many for thinking about and experiencing the world, which has now become a cultural obsession. Cinema, for example, has become a simple representation of reality—consider the countless online videos where professionals dissect and analyze whether film scenes accurately reflect their respective fields, as if assessing a film's value based on how "seriously" it represents the world outside. How “real” is the film? Just ask the expert.

We often believe that art should somehow remain faithful to our reality by representing it, but art has the potential to expand this understanding of reality, to create possibilities that we cannot yet see or imagine, bypassing representation entirely. In painting, artworks can force us to see beyond the represented and the representable, unveiling a depth of visibility that stretches far beyond what is immediately visible and recognizable—and thus beyond what can be easily represented. To experiment with art, whether as an artist or a spectator, is to actively explore the possibilities it opens up for new ways of thinking and sensing, outside the clichés, the representations and the repetitions.

In the history of art, painting has often been viewed as a medium for capturing the visible world—objects, landscapes, human figures—rendered in a manner that can be easily recognized and understood by the viewer. However, a more profound function of painting has always lurked beneath the surface: the ability to render visible the invisible forces that shape, distort, and animate the world around us. This aspect of painting, which goes beyond representation, seeks to capture the essence of forces that, while they might be felt or experienced, are not directly observable. In this sense, painting becomes not just a mirror to reality but a means of making the invisible visible, of revealing the underlying dynamics that govern our reality.

The challenge of capturing these invisible forces in painting can be likened to the task faced by composers in music. Just as music renders nonsonorous forces sonorous—conveying the intangible flow of time, the tension of emotion, or the gravity of an experience—painting brings to light forces that are inherently non-visual. These forces include the passage of time, the weight of gravity, the pull of inertia. The painter’s task is to translate these unseen dynamics into a visual language that can be sensed and felt by the viewer, even if they cannot be directly observed.

This endeavor to capture invisible forces is not new. Throughout history, artists have grappled with this challenge in various ways. For instance, in the 19th century, Jean-François Millet, when criticized for depicting peasants carrying a religious offering as if it were a sack of potatoes, defended his work by explaining that he was not focused on the difference between the objects, but rather on the shared force of weight they carried. Millet was less concerned with the objects themselves and more with the physical force that they both carried. This focus on force over form marks a significant departure from the traditional approach to painting, which prioritized accurate visual representation.

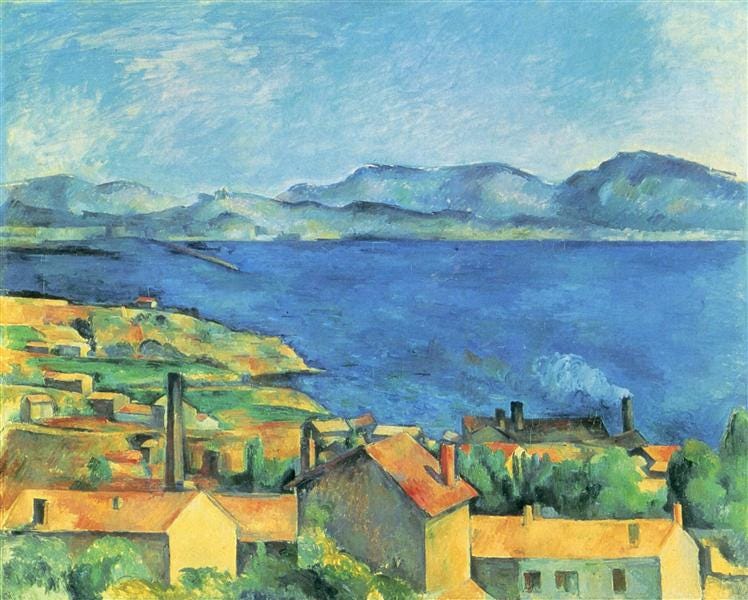

Similarly, Paul Cézanne’s work can be seen as a masterclass in capturing the invisible forces that shape the visible world. Cézanne was less interested in the literal depiction of a landscape or a still life and more in the forces that gave these scenes their character and form. He sought to capture the bending power of mountains, the life-giving potential of a seed, or the thermal energy of a landscape under the sun. His brushstrokes, which often appear deliberate and almost sculptural, are not just marks on a canvas but attempts to render these forces visible, to give them form and presence.

Vincent van Gogh took this exploration of invisible forces even further. In his hands, a simple sunflower was transformed into a dynamic force of nature, imbued with an intensity that far exceeds its literal form. Van Gogh’s sunflowers are not just representations of a plant; they are visual embodiments of the forces of growth, vitality, and even madness. He invented new forces through his use of color, texture, and line—forces that resonate on a level far greater than the surface of the canvas.

In the work of Francis Bacon, we see a very powerful exploration of this concept. Bacon’s paintings are not concerned with traditional representation or with the depiction of movement or emotion. Instead, they are focused on making visible the invisible forces that act upon and through the human body. His Figures are not static representations of people but dynamic embodiments of the forces that distort, press, and stretch them. The Figure is not a depiction of an individual, but of forces, sensations, that reveal different levels of a body.

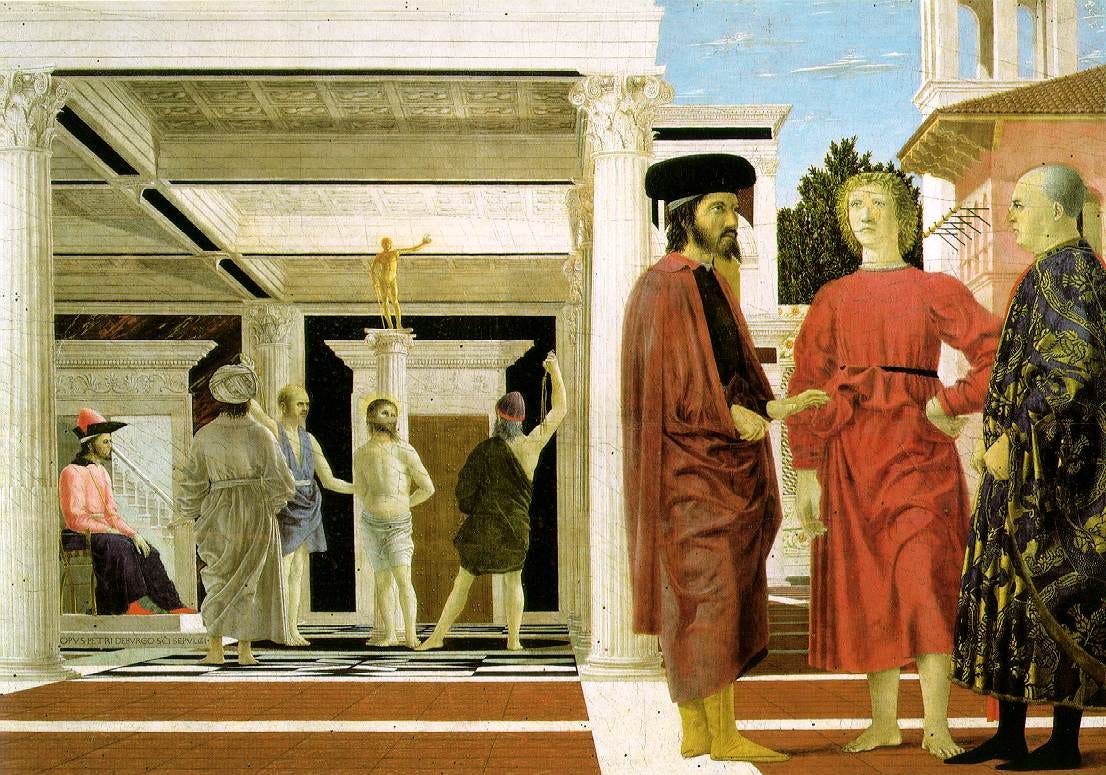

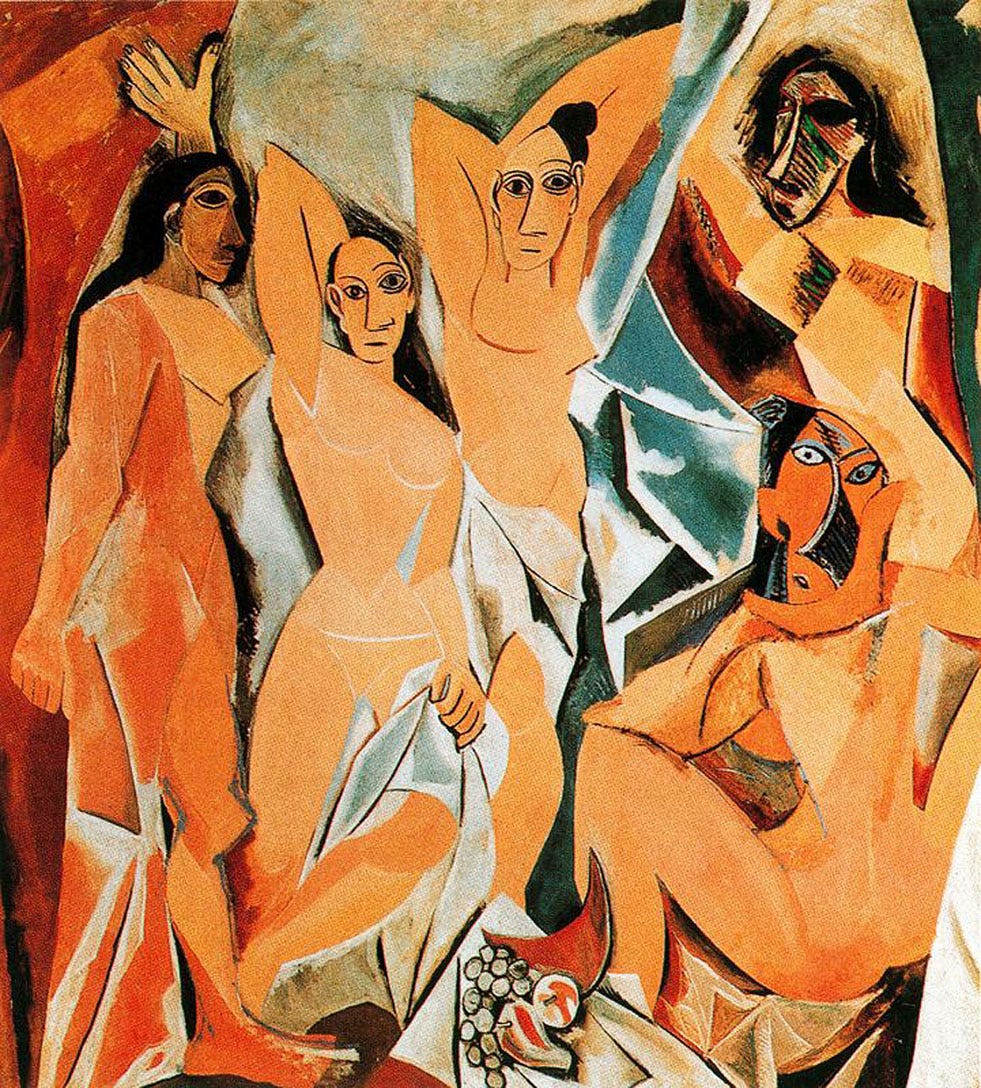

As philosopher Gilles Deleuze notes in his book Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, Bacon’s approach to painting is primarily concerned with the underlying forces that give rise to visual effects, such as movement and color. While much of modern art emphasizes breaking down and rearranging elements, Bacon's approach is different. For instance, Renaissance artists concentrated on breaking down and reassembling depth to create the illusion of three-dimensionality on a flat surface. Cubist artists, like Picasso and Braque, dissected and reconstructed movement, presenting multiple perspectives within a single image. Bacon, however, is more interested in directly capturing the invisible forces—such as pressure, tension, and contraction—that shape these elements.

For Bacon, the task of painting is to confront and capture these invisible forces head-on. This is particularly evident in his series of heads and self-portraits, where the figures are subjected to intense forces of pressure, dilation, contraction, and elongation. These forces are not the result of movement in the traditional sense; bodies do not appear to be moving through space. Instead, they are distorted by the forces acting upon them, forces that seem to strike from multiple angles, pressing and pulling the features into unnatural shapes.

This distortion is not about transformation—where one form morphs into another—but about deformation, where a single form is subjected to forces that alter its appearance without changing its fundamental nature. Deformation, in Bacon’s work, is always bodily and static, rooted in a specific moment and place. It subordinates movement to force, capturing the exact moment when the body is twisted or stretched by an external or internal pressure. This focus on deformation rather than transformation is what gives Bacon’s work its intense, almost visceral quality.

One of the most striking examples of Bacon’s exploration of these forces is his depiction of the scream. The scream, in Bacon’s work, is not just a sound made visible but the visible manifestation of an intense internal force. The open mouth, contorted face, and twisted features are not merely the result of a loud noise but the expression of an invisible force that convulses the body from within. Bacon’s scream is not about representing the horror of a particular scene or the pain of a specific experience; it is about the raw, uncontainable force that drives the scream, a force that we cannot sense or see, and yet it is a profoundly real force.

In capturing the scream, Bacon is not interested in illustrating the external cause of the scream—whether it be fear, pain, or shock—but in depicting the internal force that drives the scream out of the body. This force, which cannot be seen or heard, is made visible through the distortion of the figure, the contortion of the face, and the raw energy that seems to pulse through the painting. Bacon’s scream is not about the visible world; it is about the invisible forces that shape our experience of that world.

In this sense, Bacon’s paintings are less about depicting the world as it is seen and more about revealing the world as it is felt. His work captures the invisible forces that press upon us, that shape our bodies and minds, that distort our perceptions and twist our realities. By making these forces visible, Bacon challenges the viewer to confront the unseen dynamics that govern our lives, to recognize the power of the invisible in shaping the visible world.

Painting unburdens us from the need to represent, opening up new ways of engaging with our world and understanding it. It releases us from the obligation to remain faithful to how we currently see and comprehend reality. At its core, painting is about making visible what cannot yet be represented, about giving form to what resists representation.

Can language resist the urge to represent? Is it a means for communication, for describing the world and invoking concepts? What invisible forces are at play within it? More on this next week.